We Need to Rediscover that Numbers Aren't Everything

If thou gaze long into an algorithm, the algorithm will also gaze into… well, not exactly thee, right? More like a patchy portrait of your likeness churned out by a mimeograph low on ink—sharply delineated in a few areas, sure, but hazy and obscure in many others.

Yet close enough in the broad strokes to serve as a makeshift Rorschach test for those who believe a selective data set can provide the imprimatur of scientific detachment to a conclusion in search of confirming evidence.

Back in 2013 an “Industry Insights” report published by IBM estimated there were 2.5 quintillion bytes of data created every single day. That’s the number one followed by eighteen zeroes and drawn from “sensors used to gather shopper information, posts to social media sites, digital pictures and videos, purchase transaction, and cell phone GPS signals to name a few.”

Now, five short years later, the ante has been upped considerably. In 2017, Forbes reports, “more personal data was harvested than in the previous 5,000 years of human history”—an impressive figure considering the Sumerians of Mesopotamia only invented the written word 5,500 years ago.

Go back any further and we’d have to start arguing over whether the European Union’s new General Data Protection Act requires us to erase Paleolithic cave paintings in France.

Big Data's boosters

This, friends, is the grist that feeds the much-ballyhooed mill we call Big Data—and its boosters are legion. In fact, a writer for App Developer Magazine recently fretted that “less than 0.5 percent of that data is actually being analyzed for operational decision making.”

But is it really a positive development to find our data points tossed to and fro in oceans of petabytes, exabytes, zettabytes, and bytes likely so vast they can not yet be named, occasionally to be fished out by some technocratic administrator or another to determine whether we’re worthy for a loan, an education, a job, an insurance policy, an early release from jail?

“We risk falling victim to a dictatorship of data, whereby we fetishize the information, the output of our analyses, and end up misusing it,” Viktor Mayer-Schönberger and Kenneth Cukier warn in Big Data: A Revolution that Will Transform How We Live, Work, and Think. “Handled responsibly, Big Data is a useful tool of rational decision-making. Wielded unwisely, it can become a tool of the powerful, who may turn it into a source of repression, either by simply frustrating customers and employees, or, worse, by harming citizens. The stakes are higher than is typically acknowledged.”

Hmm. Seems like perhaps something of an understatement?

It also raises the question, what’s the next new thing? It’s one thing to blithely click “agree” on a social media user agreement; it’s quite another to have the information gleaned from there married to location data from your cell phone and facial recognition systems embedded in advertising.

Despite the velocity of change and the abstruseness of this digital architecture, we have largely placed our trust in the benevolence and good intentions of those who either constructed or administer these contrivances—without realizing how much flesh and blood creator has ceded to a machine.

Once gone will we ever get it back?

The tyranny of the collective

Towards the end of his expansive, mind-bending tome Antifragile: Things That Gain From Disorder, acclaimed statistician/scholar/essayist Nassim Nicholas Taleb goes on an extended and convincing riff about the many ways “the abundance of data” can be “extremely harmful to knowledge.”

“More data means more information, perhaps,” he writes, “but it also means more false information.” Taleb illustrates his warning by asking us to imagine “distinction between real life and libraries.”

“Someone looking at history from the vantage point of a library will necessarily find many more spurious relationships than one who sees matters in the making, in the usual sequences once observes in real life,” he explains. “He will be duped by more epiphenomena, one of which is the direct result of the excess data as compared to real signals.”

Now hold on a second, you say, libraries have done alright by me!

Yes, of course. But we’re not talking about your local or university library in which the curation process is driven by compounding human consensus and diversity. This is more akin to being ushered into a theoretical library full of books chosen by an entity possessing a singular presupposition and devoted to a very specific agenda or agendas. Any volume that challenges or offers contrary evidence is ignored or discarded.

If you’d like to personalize this thought experiment even further, imagine all of these books are volumes detailing how your life should be run, what you should be allowed to do, the degree of trust you should be granted.

“The researcher gets the upside, truth gets the downside,” Taleb posits. “The researcher’s free option is in his ability to pick whatever statistics can confirm his belief—or show a good result—and ditch the rest. He has the option to stop once he has the right result.

“The spurious,” he adds, “rises to the surface.”

Big Data raises this “cherry-picking to an industrial level,” Taleb argues, adding: “Modernity provides too many variables (but too little data per variable), and the spurious relationships grow much faster than real information, as noise is convex and information is concave.” We find ourselves, he fears, at the mercy of a “tyranny of the collective,” made all the more formidable by those daily quintillions added to its mass.

Beware mathematicians bearing magic formula

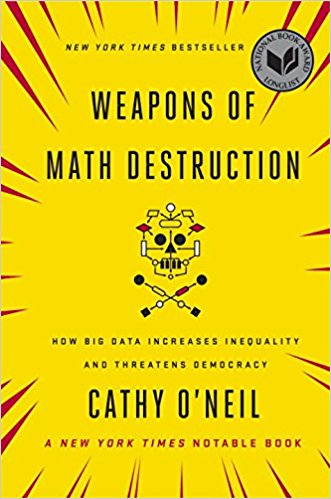

“When I was a little girl, I used to gaze at the traffic out the car window and study the numbers on the license plates,” Cathy O’Neil writes in the opening chapter of her always elucidating, frequently harrowing 2016 book Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy. “I would reduce each one to its basic elements—the prime numbers that made it up. 45 = 3 X 3 X 5. That’s called factoring, and it was my favorite investigative pastime.”

Not exactly the sort of material that’ll send folks into wistful exclamations of “Hey, kids will be kids!,” but for O’Neil math “provided a neat refuge from the messiness of the real world.” She went to math camp, followed numbers into college, eventually got her Ph.D. “My thesis was on algebraic number theory,” she writes, “a field with roots in all that factoring I did as a child.” She got a tenure-track gig at Barnard then made the jump to the hedge fund D.E. Shaw to “put abstract theory into practice.”

“At first I was excited and amazed by working in this new laboratory, the global economy,” she writes. Then, a little more than a year later, came the 2008 crash which “made it all too clear that mathematics, once my refuge, was not only deeply entangled in the world’s problems but also fueling many of them.”

“The housing crisis, the collapse of major institutions, the rise of unemployment—all had been aided and abetted by mathematicians wielding magic formulas,” she continues. “What’s more, thanks to the extraordinary powers that I loved so much, math was able to combine with technology to multiply the chaos and misfortune, adding efficiency and scale to systems that I now recognized as flawed.”

Yet in what should have been a humbling moment for her field, she notes in the aftermath, “new mathematical techniques were hotter than ever and expanding into still more domains.”

Without any real discussion and a tacit approval seemingly based purely on awe, humanity had surrendered to techno-deities and “like gods, these mathematical models were opaque, invisible to all but the highest priests in their domain: mathematicians and computer scientists.”

If this seems like hyperbole before you read Weapons of Math Destruction, it certainly won’t by the time you finish it.

From chasing excellent teachers out of failing public schools where they’re desperately needed to keeping qualified applicants out of good jobs and educational institutions to calculating the potential recidivism of inmates in dubious ways that keep the reformed as wards of the prison-industrial complex to creating false feedback loops that reinforce and amplify inequality and limit social mobility to preventing us from advocating for ourselves in the very political system that frequently appears determined to foist all of this upon us, O’Neil makes a convincing case that we should all begin and end our days acknowledging, There but for the grace of the algorithmic gods go I…

“[Y]ou cannot appeal to a WMD,” she writes. “That’s part of their fearsome power. They do not listen. Nor do they bend. They’re deaf to charm, threats, and cajoling but also to logic—even when there is good reason to question the data that feeds their conclusions.”

From her perch at the Mathbabe blog, through her books, and in a bracing TED Talk entitled “The Era of Blind Faith In Big Data Must End,” O’Neil has established herself as an eloquent advocate for humanity in the face of technocracy.

“Models,” she warns we laypeople, “are opinions embedded in mathematics.” Ah, but therein lies the rub. What incentive does any person or institution that benefits from a given algorithmic outcome to acknowledge to themselves or anyone else that the dispassionate automation that got them to it is a fiction, polite or otherwise?

What’s at stake

Of course, none of this is new. When in Ecclesiastes it is said that, “God made men upright, but they have sought out many devices,” it’s not a reference to iPhones and supercomputers…though it easily could be updated as such. Nor is the state of affairs hopeless. It simply requires more honest grappling and pushback than what has hitherto occurred. For that to happen we must first set aside a bit of convenience and have a frank discussion of the stakes.

“The essential point about big data is that a change of scale leads to a change of state,” Mayer-Schönberger and Cukier write. “[T]his transformation not only makes protecting privacy much harder but also presents an entirely new menace: penalties based on propensities. That is the possibility of using big data predictions about people to judge and punish them even before they’ve acted. Doing this negates the idea of fairness, justice, and free will.”

One hopes those remain universal ideals we can all come together to defend.

Disclosure of Material Connection: Some of the links in the post above are “affiliate links.” This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, we will receive an affiliate commission. Regardless, we only recommend products or services we use and believe will add value to our readers. We are disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.